Ungigging

The gig rider

A delivery rider leaves his flat and shuffles his bike downstairs. Once outside, he begins a three-mile cycle to Camden, where he reckons he'll work for the evening.

As soon as he gets there he logs into the app, which presents him with a banner saying "Blue Delivery Company: Changes to Supplier Agreement." He taps it and scrolls through the text. It's all pretty familiar: "...self-employed contractors supplying delivery services... payment per delivery... not a relationship of employment."

The only bit of the contract that he'd not seen before is the "right to appoint a substitute", which as far as he can tell lets riders rent their accounts out to randomers. It's always happened, but it's a bit surprising that the company are okay with it. A lot of the guys who rent accounts don't have the right to work in the UK. Doesn't bother him. Live and let live.

He scrolls to the end of the page, hits accept, and waits for jobs to come in. The first hour is good. Four deliveries, each less than a mile. £16 all in.

The next hour and a half is awful. He spends thirty minutes flicking between different delivery apps waiting for a decent job. Long journey up Highgate Hill for £3? - no thanks. McDonalds? - no thanks. It's the best thing about being a contractor, getting to decline McDonalds, with the long waits for cold food, with the disrespect from their staff. That's the advice everyone gives you when you join: avoid McDonalds.

After a bit of waiting, an order from a vegan barbecue restaurant comes through. He cycles over and joins the queue of delivery riders inside. His order will be ready in five minutes "definitely". Ten minutes pass. It's hot in the waterproofs. No water or anything for riders in here. No seats either so they're all standing.

Half this job is waiting, for jobs to come through, for food to be ready. And they aren't paid to wait. How long is this going to take? He should have cancelled the job after ten minutes of waiting. That's his rule. He's stayed too long to cancel now. Sunk costs.

He gets the food after 28 minutes - "Sorry, busy night". He rides to a house in Primrose Hill, running a few lights to make up some time. "Mate, it's been ages since we ordered." No tip.

He earns about £6 for that hour and a half, and his numbers don't really recover for the rest of the night. Come 1am, he's cold so he cycles home. £58 total, about £9 an hour. Less than minimum wage at £9.50 but pretty normal for a Tuesday.

If only he'd cut his losses at that restaurant. Fine margins, this job. And the money's definitely getting worse. Maybe he should get some salaried shifts at the Red Delivery Company. Life'd be more predictable at least.

The salaried worker

Earlier that same evening, elsewhere in London, another rider is getting ready to head out. He's wearing Red Delivery Company clothes, top to toe, even the helmet. After leaving the house, he cycles a few miles on his company e-bike to Camden, his shift zone for the night.

He'll be working from 7pm until 2am. People like this shift - not too quiet, not too busy. £10.50 an hour as a "salaried worker", employed by an agency who give him sick pay and a pension. Not that bad.

And he'd rather this than the mad rush of being a contractor, though they all claim to be earning more than him, and they don't have to put up with a lot of the bullshit that he does. The terrible app. The terrible rider support. The no turning down of orders. The bullshit starts early this evening. His first hour is nothing but McDonalds deliveries. It's as expected: long waits for cold food.

After an hour or so on shift, there's an order from a vegan barbecue restaurant. He joins the queue of riders waiting to pick up. The girl at the counter says "five minutes".

Ten minutes later he notices Blue Riders getting jumpy, agitated, at the wait. He's not too bothered. He's still getting paid. Worst case, he'll get a call from one of the faceless monitoring people, "we notice you've been slow. Please sort it out or you'll be deprioritised for shifts'."

Twenty minutes pass before he gets the food. He cycles it over to a house near Regent's Park. He doesn't run red lights or undertake cars or ride pavements. He doesn't go in for any of that. What's the point in saving a couple of minutes if the pay's the same?

After he makes that delivery, the jobs slow right down. A lot of waiting. And come 1am, he's cold and tired and wants to go home, but he can't. Maybe he should switch to contracting. Leave whenever you want. Turn down the bad jobs. Rent your app out to some mates. Bit more of a thrill to it all. Maybe he'd care more. Maybe.

Ungigging: the end of the gig economy

Employment status matters in the gig economy. It affects those vital organs of working life: how you get paid, how much you get paid, and how free you are at work.

The Red and Blue stories are based on a recent interview of mine with a delivery rider. I hope they give some sense of the differences between the two employment statuses. Bear these differences in mind. They are important for what we're going to talk about next: the ungigging of the UK takeaway delivery sector.

When I say ungigging, I mean the end of the contractor model as the default way of delivering takeaways, the end of paying riders for each delivery they make rather than an hourly wage, and the end of riders being given broad freedoms in how they go about their work.

I think these changes lie just around the corner, and the rest of this letter explains why.

How many gig delivery workers are there?

Before we poke around in the dysfunctions of the contractor model, let's look at how the big three delivery companies - Just Eat, Deliveroo, Uber Eats - currently hire riders.

The first thing to say is that wage-earning riders are by far the minority. Uber Eats and Deliveroo remain addicted to the contractor, payment-per-delivery model; in the UK, you cannot join the waterproofed ranks of their tens of thousands of riders without being a contractor.[1]

Just Eat takes a more ecumenical approach. If you want to ride for them in London or other UK cities, you can choose whether you want to be a "salaried worker" or an "independent contractor".[2] Just Eat's 2022 annual report mentions 8,000 (full-time equivalent) global salaried couriers, up from 7,000 in 2021.[3]

Salaried workers are, then, a small but growing minority of Just Eat's c.200,000 global couriers. But they have a symbolic importance beyond their number. They show that app-based delivery can be made to work without relying on contractors; if the contractor model dies, the salaried riders are the future.

For the wages of sin is death

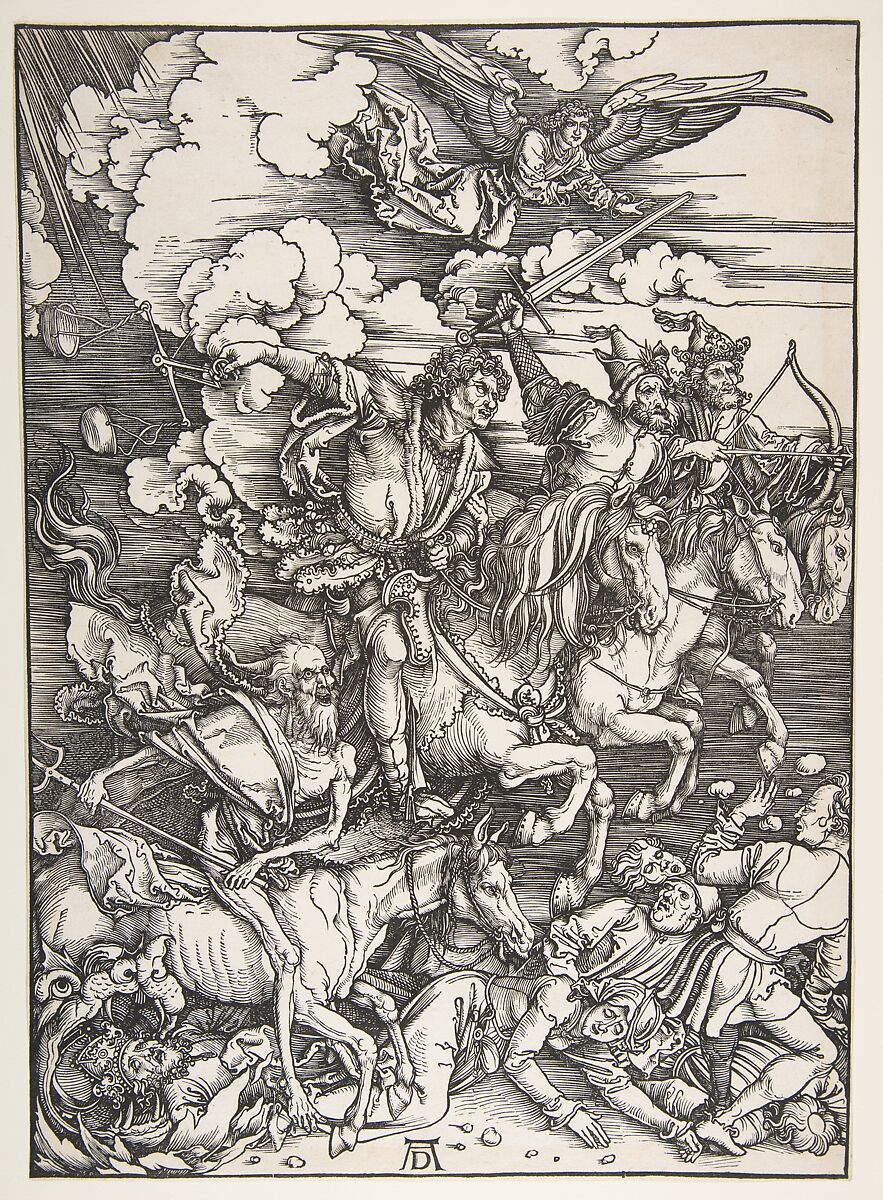

What would the end of the gig world - the end of the contractor model - look like? I suspect that it'd be an apocalypse in the Biblical sense, where a world that has lapsed into sin is at once punished and cured by divine intervention.

In this case, the gig world's sins are twofold. First, average contractor pay is dipping below the minimum wage. Second, the contractor model is inherently vulnerable to abuse, principally by riders working for delivery companies without having the right to work in the UK.

As for the divine punisher of these sins, lift up thine eyes to the next Labour government. The Labour Party has made no secret of its desire to reform the gig delivery sector.[4] And once installed in government, these twin crises of low pay and abuse will make reform all but inevitable.

Sodom and Gomorrah afire, by Jacob Jacobsz. de Wet d. J., probably Köln, c. 1680, oil on canvas - Hessisches Landesmuseum Darmstadt - Darmstadt, Germany

Gig economy pay

The delivery companies have a low pay problem. A study in 2021 found that more than half of Deliveroo riders were earning less than £10 an hour while out and about.[5] Since then, pay has been falling; the past year has seen delivery fees fall between 8.4% and 13.8% in real terms.[6] It's fair to assume that hourly contractor pay is now right on the borderline, or just below, the £9.50 minimum wage. Some will earn more, others less.

The fall in rider compensation has been driven by shareholders urging the delivery companies to cut costs.

Uber, Deliveroo, and Just Eat have had a similar few years: frothy share prices in the summer of 2021 were followed by valuation crashes in the autumn of that year.

Since then, shareholders have demanded that these companies, which have never turned a profit, get serious about cash flow and routes to profitability. This is a tough ask in a sector where companies were often losing money per delivery. In such circumstances, growth alone would not be enough to turn a profit. The companies would have to raise prices and cut costs.

The former has proved difficult. The food delivery market is too competitive to allow for big price increases. This has left cost cutting as the only viable route to profitability. And the biggest cost to cut is rider pay. The fall in delivery fees is, therefore, not exactly surprising.

Why does falling rider pay matter? In any ordinary business, the principal risk of cutting pay is that good staff leave. In the gig business, that risk exists, but it's also joined by a more profound and existential risk, that of government intervention.

As long as most contractors consistently earn more than the minimum wage, then the delivery companies can quite reasonably make the case to the public and to Parliament that there is no sin being committed, that the contractor model is not being used to flout minimum wage regulations, and therefore that there is no need for state intervention.

But the data suggests that contractor pay is already descending underneath the waterline of the minimum wage. And if pay stays underwater, then the force of the delivery companies' argument is lost.

Instead, the contractor model begins to look less innovative and more exploitative - a capitalist ruse for dodging minimum wage laws. Give it enough time, and the government will soon feel obliged to dive in and intervene.

DALL-E

DALL-E

Why ride for less than minimum wage?

One of the surprising things about these pay cuts is that the delivery companies don't seem to be having problems finding enough riders. If they are regularly paying contractors less than the minimum wage, then you'd expect the contractors to stop riding and get another job. After all, in today's tight labour market, minimum wage workers are in high demand.

But this rider exodus doesn't seem to have happened. Something is propping up the supply of labour, and I'm not sure what it is.

Perhaps riders so value the freedom of the job that they are happy to earn less than the minimum wage doing it. Perhaps the pay data is wrong.

Deliveroo, Just Eat, and Uber Eats accounts for sale: a theory of account renting

Another theory, however, can be found on the reddit forums where some riders spend their time. This explanation concerns the practice of account renting, where contractors appoint substitutes to perform their jobs for them. Riders say that the system is being abused.

Most of the time, account renting works by a rider sharing his delivery app log-in details with someone else. He'll negotiate a fee with the renter for doing so (something like 5% of earnings, or a fixed sum to have the account forever).

This is all perfectly above board. The riders' contracts give them the express right to appoint someone else to do their job.

The trouble is that the delivery companies have no idea when an account is being rented out. They also have no idea who the account renter is. Have they been banned from these apps already? Do they have the right to work in the UK?

The rider forums are full of allegations that accounts are being rented out, with no scrutiny, to people without the right to work in this country, to children, to drug dealers, to criminal gangs.

And if these allegations are true, then they constitute the second great sin of the gig world.

They would also partly explain the resilience of rider supply in the face of pay cuts. The minimum wage is largely irrelevant to this shadow workforce. They cannot get formal employment elsewhere, and so they continue to ride when pay drops below the minimum wage threshold. This is a gift to the delivery companies, who can nudge delivery fees down without hurting output.

Background checks

All of this talk of shadow workforces seems shaded by conspiracy. It would be crazy - wouldn't it? - if Uber (market cap: $67.71 billion), Just Eat (€4.53 billion), and Deliveroo (£1.45 billion) allowed their riders to appoint substitutes freely without making sure that formal background checks had been completed on the substitute.

The companies' apparent naivety only makes sense in the light of some recent litigation between Deliveroo and the Independent Workers' Union of Great Britain (IWGB), the gig economy trade union.

In 2017, IWGB brought a case to the Central Arbitration Committee, an industrial relations tribunal. The union argued that Deliveroo riders should be treated as "workers" and not "self-employed contractors". If Deliveroo were to lose, it would open the door to all of its riders being protected by minimum wage legislation.

In 2017, weeks before that case went to the tribunal, Deliveroo changed the terms of their contracts with riders. The old contracts had allowed riders to appoint substitutes but only if those substitutes were already registered Deliveroo riders.[7]

The new, amended contracts said that riders could appoint pretty much anyone to work in their place as a substitute (even if they didn't have a Deliveroo account) provided the rider vetted the substitute themself.[8]

Deliveroo's lawyers then argued in the courts that this new and expanded right of substitution meant that riders were "self-employed contractors" and not "workers". Every tribunal, including the Court of Appeal in 2021, agreed with Deliveroo.

But to win on this self-employed contractor point, Deliveroo has been forced into giving riders free reign, with all of its consequences, to rent out their accounts. A victory at a significant cost, and one that may set in motion a later defeat, a Borodino moment.

The delivery companies are in a bind. If they scrutinise account renters - say, by performing thorough background checks - then they both increase their administrative costs and intrude upon the account holders' right to rent out their accounts freely. And they intrude upon that right at their peril; as the courts have said, this right is what makes the riders contractors and not workers.

Perhaps it suits these companies to avert their eyes from dodgy renting practices, to assume that the contractors have the time and means and will to vet their own substitutes properly; more riders means more money. But the political and regulatory risks of looking away are obvious. A corporate crisis percolates.

The end times

The Four Horsemen, from "The Apocalypse", Albrecht Dürer (1498)

The problems facing the gig giants look impossible. To become profitable, they must cut rider pay. But the more they cut, the more the whole business model looks like a scheme to avoid paying the minimum wage.

To stop abusive account rental practices, they must stop riders from renting out their accounts, or they must start vetting the substitutes themselves. But the more of these controls that the companies exert, the more they risk a court finding that the riders are not contractors but workers, entitled to minimum wage protections.

If Uber, Deliveroo, and Just Eat cannot resolve these problems themselves - and I don't think they can - then in all likelihood the next Labour government will do it for them. The intervention would probably take the form of extending minimum wage protections to contractors. This fits with Starmer's instincts: government by legalistic tinkering.

Though a small change, bringing in minimum wage protections would probably kill the contractor model. I don't see how its current freedoms could survive:

- At the moment, contractors are free to log into multiple apps: which app would pay the minimum wage?

- At the moment, contractors are free to reject jobs they don't want to do: how could a delivery company justify paying an hourly wage to a rider who regularly turns down jobs?

- At the moment, contractors can log on and off at will: what would stop riders from only logging in (and earning their wage) at quiet times and in quiet places?

Instead, these freedoms would be replaced by the ordinary, grey controls of minimum wage work. Prescribed times and places for logging in. No turning down work or running multiple apps at the same time. Uniforms.

Of course, the worst bits about the contractor model would go, too. The unpredictable and often below minimum wage pay. The lack of pension and sick pay. The exploitation of vulnerable people. All the unpaid waiting around. The experience of having your income undercut by those who don't have the right to work in the UK.

Yet despite all of this, it's difficult to escape the sense that something will have been lost if gig riders are replaced by salaried workers. After all, the autonomy that these contractors have is so rare in jobs at this pay bracket. Talk to anyone that's done delivery riding and you'll see how much that autonomy matters; many riders put considerable store by their identity as contractors, as nightriders who could come and go as they please.

But the good times of gig work, where you could earn fairly decent money with little oversight, were always unsustainable. It was a freedom that was propped up by loss-making tech companies and their venture capital dollars.

Those companies have now turned their attention to making money, principally by putting the squeeze on rider pay. And in so doing, not only have they spoiled the contractor party, but they are also heading straight for a bust-up with the state, with consequences that may well unravel the gig economy in its entirety. Let's see what happens.

If you've enjoyed this newsletter, please forward it on.

And if you aren't yet subscribed, please subscribe

https://www.uber.com/gb/en/e/deliver/london-eng-gb/ and https://riders.deliveroo.co.uk/en/apply ↩︎

https://www.dailyrecord.co.uk/news/politics/labour-pledges-end-gig-economy-24619862 ↩︎

https://www.thebureauinvestigates.com/stories/2021-03-25/deliveroo-riders-earning-as-little-as-2-pounds ↩︎

https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/deliveroo-uber-eats-just-eat-takeaway-gmb-union-b2262750.html?amp&fbclid=IwAR3lOWo7bmkekFjDyoApw4LGdbo7kITYl1x-xw4omMeoIUCyghhdAJuTjBI ↩︎

R (on the application of the IWGB) v CAC and Roofoods Ltd t/a Deliveroo: https://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWCA/Civ/2021/952.html footnote 3 ↩︎

ibid. para 17 ↩︎