the future of UK farming

This week, Jacob Rees-Mogg was shuffled into the post of Minister for Brexit Opportunities and Government Efficiency. I think people on TikTok call this 'manifesting': "If we create the job title, surely the opportunities and the efficiency will come?"

If I was Rees-Mogg, I'd look for Brexit opportunities in the places where the EU is most cumbersome and most beholden to lobbyists. State aid. Also, farming.

Leave EU? leave EU? how could they leave EU?

Since we left the EU in 2020, the Oatly-drinking bien pensants (myself included!) have done lots of good sneering at the silly British farmers. Their suffering (labour shortages, future cuts to subsidies) is a righteous punishment for their sin in voting leave.[1]

Maybe there's another way of looking at it. UK farmers benefited from our membership of the EU. They received subsidies (to the tune of 55% of farm incomes in 2015[2]) and cheap labour. But this was a toxic relationship:

- It relied on low-pay and poor working conditions for Eastern European workers.

- The subsidies were both unfair - with 80% of Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) subsidies going to the 20% of the biggest farms in the EU[3] - and unimaginative, based mostly on acreage rather than the farm's output / activity.

- The UK was also a net-contributer of CAP payments. We were getting much less in CAP subsidies than we were paying out to European farmers.

- This model of farming encouraged harmful over-production. When 55% of your income comes from subsidies, many more farms that would otherwise go bust are kept in the game. Food supply is kept artificially high and food prices are kept artificially low: we spend only 8% of our income on food (we spent 33% in 1957). These low food prices do not represent the true cost - in terms of actual cost, carbon cost, obesity, biodiversity loss - of British farming.

- British farmers did not get much of a say in setting the rules by which they had to play. This is a function of both the size of the EU and of the vast agribusiness lobby that is encamped in Brussels (petrochemicals, agripharma, meat-packing etc.).

A relationship can still be toxic even though you derive enormous financial benefits from it. Think of sugar daddies!

I don't know why farmers voted leave. But if they voted leave - against their immediate financial interests - because they thought that the above problems (i) mattered and (ii) were best resolved by leaving the EU (the body that had created the problems), then that seems like a pretty reasonable and worthy bet.

The problems ahead

The issues that farming has to resolve in the next few decades:

- If you remove the subsidies, many farms are nowhere near profitable.

- The government is committed to net zero. Farmers are net polluters.

- Biodiversity has taken a battering from farming over the past 80 years. This has to change.

- There are powerful reactionary forces that might resist reform: consumers have become used to the status quo of low food prices (supported by farm subsidies); farmers have become used to high subsidies; the intoxicating vision of the English countryside as a pastoral countryside.

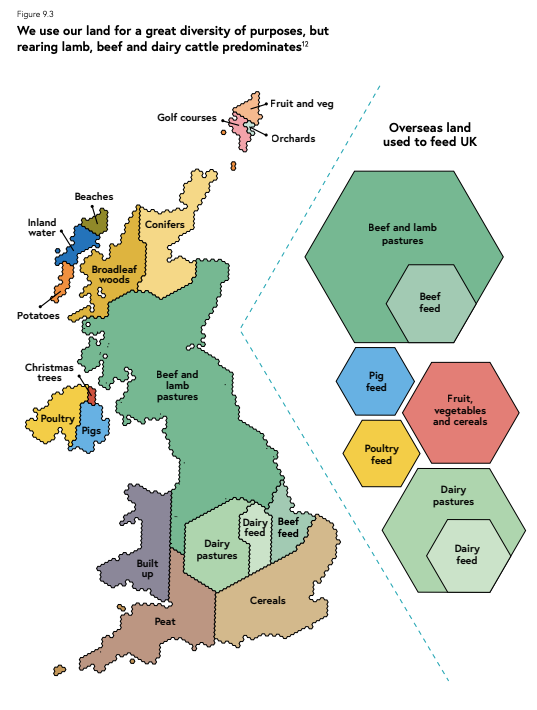

- A barmy amount of our land is devoted to ruminants (lamb, beef and dairy cattle). This pastoral farming produces large amounts of methane and carries an opportunity cost - the land grazed by animals is prevented from sequestering carbon and supporting biodiversity. You can think of ruminants as the coal of the food world; the UK may be suited to pastoral farming and mining coal, but that does not mean that we should build our food and energy systems around these activities.

This graphic used in Henry Dimbleby's excellent National Food Strategy Report is a really good illustration of some of these problems (pp. 89-91):

Note:

- Look how much is livestock!

- Fruit and veg take up the same amount of land as golf courses (5x more land is devoted to golf courses than orchards).

- Poultry and pigs are relatively land- (and carbon) efficient sources of meat.

- The built-up areas are quite small.

What are we doing to address these issues?

Since leaving the EU, the government has so far committed to the following:

- The phased removal of the old CAP-style subsidies (known as the Basic Payment Scheme).

- The introduction of new pilot subsidies based on worthy actions: (1) the Sustainable Farming Incentive (subsidies given to farmers that do stuff to lower emissions, flood risks etc.); (2) Local Nature Recovery (restoring natural habitats, like hedges etc.) ; (3) Landscape Recovery (subsidies for re-wilding).

- Grants / loans for a range of capital investments. Here's a summary.

A thought experiment

What would farms look like if you adopted a fairly radical package of measures?

Let's include: (i) removing subsidies based on acreage; (ii) introducing a tax on beef and lamb paid for by consumers; (iii) the introduction of new subsidies for re-wilding and carbon sequestration projects; (iv) the introduction of new subsidies for capital investment that adds value to farm products (e.g., making capital available for a dairy to turn itself into an ice-cream producer).

Having adopted these measures, let's roll the clock forward 20 years. Here are four types of farm that might survive and thrive...

four future farms

1. arable empires

The Kansas-ification of the English landscape.

Small farms are less productive than big farms (National Food Strategy Report, p.101):

71% of English farms are small or very small, taking up 28% of the land in total and producing 13% of all agricultural output. The largest farms make up only 8% of farms but occupy 30% of farmland and produce 57% of farming output.

If subsidies are removed, then the big farms will be able to hang around. In fact, they are likely to get bigger, as they gobble up the no-longer-viable smaller farms.

The more these mega farms grow, the more they can invest by setting aside profits or raising money against the value of their growing land portfolio. This capital will give them first access to the farming technology of the future: autonomous combines and tractors; robots that can kill weeds without using herbicides; robots that can plant, and then remove, nitrogen-fixing plants amongst the cash crops (lessening the need for expensive fertilisers).

These mega farms will mostly be arable or vegetable. In our imagined future, meat is taxed to reflect its true cost to the climate. At current prices, we're talking c.£12 for a packet of supermarket beef mince.[4] Demand for meat products will plummet. Demand for alternatives will rise.

The UK will look more like the USSR or the US. Its calories will come from a small number of vast farms in its arable-suited regions. Instead of the Ukraine or Kansas, think Norfolk and Lincolnshire.

The bet is as follows:

That technology can allow further intensification without the usual negative externalities (fertiliser run-offs, soil erosion etc.). If it can't, then we will be unable to repair the environmental damage that farming has already caused in Lincolnshire and Norfolk.

That technology / new techniques can allow intensification without a corresponding impact on food security:

- It's not good for food security if you have a small number of massive farms all growing the same strain of wheat and using the same herbicide (see e.g., American farmers' reliance on the herbicide RoundUp, which leaves them massively exposed to a RoundUp-resistant weed).

- But homogeneity of crops and herbicides/pesticides is not an inevitable consequence of intensification.

That the arable / vegetable suited regions will remain so suited despite climate change. On the one hand: we might benefit from sunnier weather. On the other hand: climate change might mess with the Gulf Stream. Who knows?

2. boutique

Many small to medium-sized farms, particularly pastoral farms, will be unable to make the maths work once meat taxes are introduced and subsidies removed. Some will get taken over by larger farms. Others will be taken over and run at a loss by ex-City bankers. Others will become carbon sequestration and rewilding projects.

Some of these small to medium-sized farms will survive though, and they'll do it through boutique-ification. These farms will:

- Add value to ordinary farm outputs by producing luxury goods - such as cheese, smoked meats and chutneys etc.

- Take advantage of rising food prices as food supply falls due to many small farms being knocked out by new taxes and the removal of subsidies.

- Diversify: e.g., rewilding projects that attract subsidies; a smaller ordinary dairy farm (ready to take advantage of any price rises); milk vending machines; a farm shop; cheese making; an adopt-a-cow scheme; a farm-to-consumer delivery service run by Amazon; B&Bs etc.

- Share capital costs by working in co-operatives: e.g. if dairy farming is no longer profitable by itself, it doesn't make sense for that to be the central focus of your farm. Having a smaller herd and sharing a big rotary milking parlour with other small farmers might be more sensible. Expect wine-making cooperatives in Kent and Suffolk!

The dairy farmer that I interviewed the week before last would fall into this category:

...the basic farm payment is being phased out. This year, we're getting 20% less, then next year it's 30%. It's sort of a gradual thing. I think it will knock a lot of farmers out, because it will make the work a bit more difficult. And, unfortunately, I think what it will possibly result in is farms being a lot bigger. It might be the bigger farms that survive, which is what people don't want. And we although we're 180 cows were kind of regarded as sort of medium to small. The way that we can survive is by making cheese and selling our milk at the farm gate. It is going to be tough. it's a tough road ahead.

The cultural inheritance of English farming - the patchwork fields, the drystone walls, the sheep-filled folds - will be left to these boutique farms. It will, however, be a partial inheritance; only a few of these types of farms will survive.

3. animal impersonator

Spend some time in the smoking area of any Shoreditch club and you'll find people talking earnestly about re-wilding. It's very hot right now.

The logic goes something like this...

Fact 1: we will have spare farmland:

- Pastoral farming involving methane-spewing ruminants is terrible for the planet.

- We can rely on ever-intensifying arable farms for the vast majority of our calories (especially if we give up red meat).

- We're removing subsidies that make most pastoral farming viable. We may introduce meat taxes that make it even less viable.

- A large number of pastoral farms will be knocked out by these developments.

- These pastoral farms are on marginal land, which is not suitable for arable or vegetable farming.

- Therefore, we will have a huge amount of land going spare. It doesn't make economic or environmental [can you split the two?] sense to farm that land.

Fact 2: our farming/cheap food addiction has ruined the environment:

As Henry Dimbleby's paper describes (pp.39-40), two developments led to the intensification of farming in this country.

First, the drive for self-sufficiency during WWII: we went from producing 30% of national food demand to 75%.

Second, the (un)Green Revolution of the 50s and 60s: fertilisers, herbicides, pesticides became cheap and ubiquitous at the same time as new high-yield strains of wheat and barley. Yields increased dramatically.

Boring things like soil health, mycelial networks, worms, and cover crops took a back seat to the shock-and-awe of chemical farming.

The environment suffered greatly. Bacteria died. Insects died. Fungi died. Fish died. Birds died. All pastoral poetry from before 1940 became unintelligible; no-one had seen the plants and animals that the poets were talking about: schoolchildren would say things like, "Miss, this poem is boring. Wtf is a turtle dove?"

This scene of misery is compounded by the carbon and methane that farming has pumped into the atmosphere over the years. CO2 via the production of fertilisers. Methane via ruminants.

Given facts 1 and 2: we should use the spare land to sequester carbon and restore biodiversity.

Rewilding solves both the sequestration and the biodiversity problem. It kills (or saves) two birds with one stone. Isabella Tree's Wilding and George Monbiot's Feral give a sense of what it might look like. It involves a rough simulation of the European landscape before it was substantially altered by humans. So, things like:

- Rewetting peatlands.

- Restoration of salt marshes.

- The undraining of farmland.

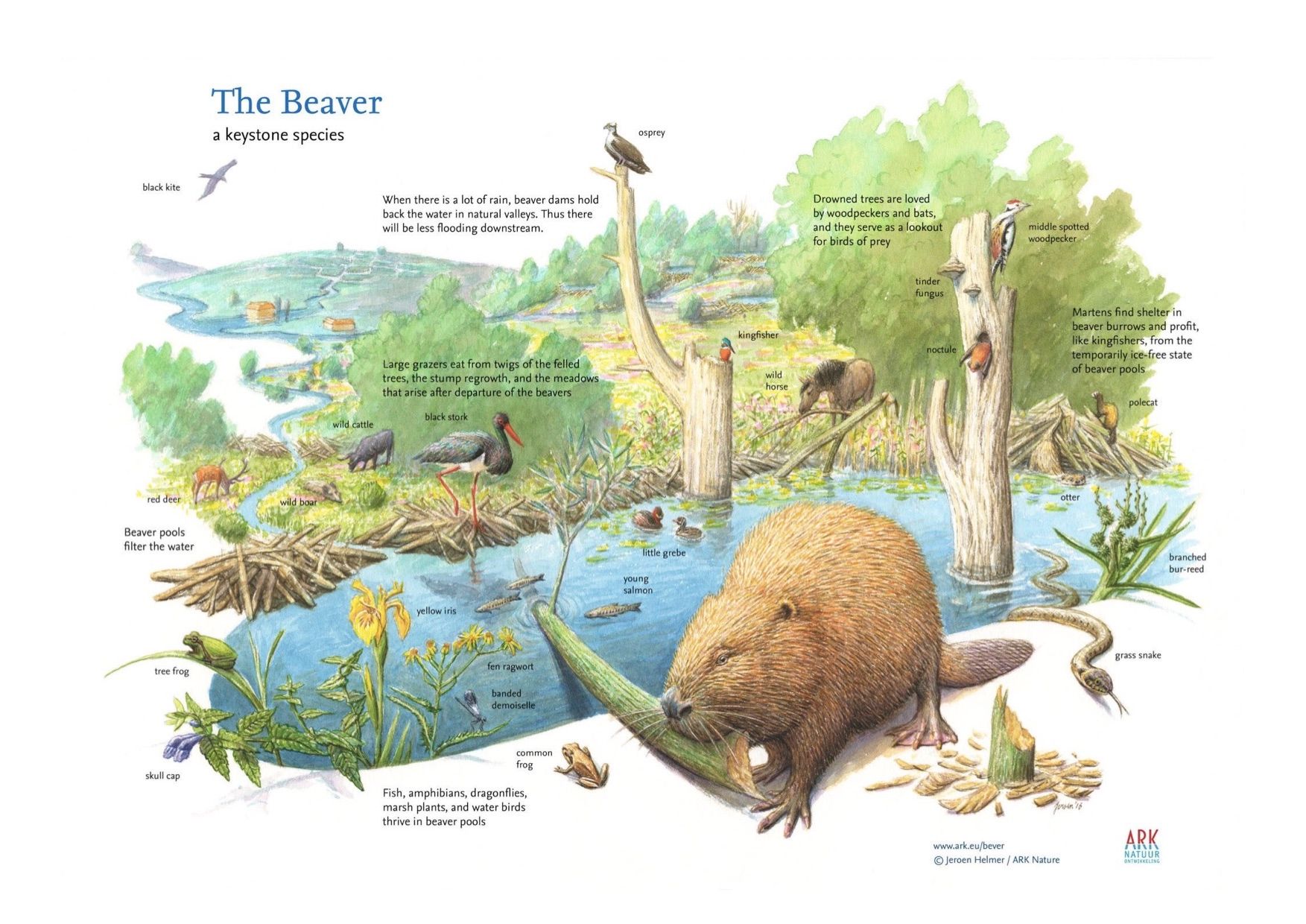

- The re-introduction of beavers to the UK. River flow is slowed by their dams, reducing the risk of catastrophic flooding.

- The removal of barriers between fields.

- The encouragement of early growth forest and scrub.

- The introduction of small roaming herds of landscape-transforming cattle. These play the elephant-like role that aurochs (extinct European mega cattle) once played in the landscape. Churning up soil. Knocking paths through the scrubland.

- The introduction of wild pigs. Again, these churn up the soil and encourage wildflower growth.

- Restoring soil health through cultivating worms and fungi.

- Ideally, the re-introduction of apex predators, such as lynx and wolves, to keep the population of pigs, deer, and cattle at sustainable levels (i.e. to levels where saplings are able to grow without being eaten). This won't happen, though.

ark.eu/bever Jeroen Helmer / ARK Nature

The roving cattle and pigs keep the forest in a perpetual adolescence, and this early growth forest is the ideal carbon sink. It sequesters much more carbon than mature forest.

Three questions follow: First, how much land will be rewilded? Second, who pays? Third, what do the farmers actually do on these projects?

how much land?

If meat consumption falls and arable farming intensifies, then there'll be a big chunk of re-wildable land - 40%, according to the National Food Strategy:

If we were to set our sights higher, increasing productivity by 30% and reducing meat eating by 35%, we could produce the same amount of food from 40% less land.

Some farms will carry out small re-wilding projects. 1000s will be devoted entirely to rewilding.

who pays?

Subsidies: The removal of greenhouse gases and the restoration of biodiversity are public goods, things of value to us all. They are suited to public subsidies.

Guilty corporations: businesses will purchase land and pay farmers to run rewilding schemes as part of their carbon offsetting efforts. This is happening now.

Some businesses will pay rewilding companies to purchase and develop (/undevelop) the land for them. Others will run their own rewilding and sequestration projects. Those running their own projects can plaster them over social media and use them for corporate away days. Fun!

Fancy meat sales: When the numbers of roaming cattle become too large, they will be culled. Farmers can sell this meat.

Eco-tourism: B&Bs etc.

what do the farmers do?

If the farmer stays and re-wilds their own farm, then they will be:

- doing lots of digger work (re-wetting, making rivers wider);

- doing lots of planting of trees;

- removing bad weeds (Japanese knotweed etc.);

- planting hedgerows;

- shooting deer, badgers, wild pigs, and cows;

- recording data for ecologists;

- managing the B&B.

A lot of this requires the farmer to pretend to be some form of animal, filling in the gaps in the partially wild system - sometimes they will pretend to be an auroch, knocking down trees and causing creative destruction. At other times, they will pretend to be a wolf, culling the excess large mammals.

This is a profound break from the past. If a farmer rewilds their own farm, their identity changes. Are they even a farmer? They are no longer master of the land exercising their dominion to produce tangible stuff. Instead, they are a servant of the land, with outputs that are less clear. This identity re-wiring will require the changing of our perceptions of what a farm looks like and does.

4. factory to fork

If we move to a system where the carbon cost of food is reflected in its price, then farmers have two mechanisms for pushing down the price of their goods. They can reduce the actual costs (feed etc.) of producing the meat. They can also reduce the carbon costs.

Using farms that resemble factories is one way of reducing both costs. This is already happening in China, with the construction of 12-storey pig farms.

In our imagined future, multi-storey pig farms and chicken farms will start to pop up in the UK, too. It's not palatable from an animal welfare perspective, but over time we'll be worn down by the arguments of the meat lobby: this is the only way to make green eggs and ham. If such factories are better at preventing diseases in animals then surely that's better for their welfare? Can a pig even comprehend what it means to be inside or outside?

These farm factories will be accompanied by factories producing lab-grown meat.

The tiering of meat that we see at the moment (organic, corn-fed etc.) will be exacerbated by these changes. We'll have a new top tier: ruminant meat reared on boutique and re-wilding farms. And a new bottom tier: cheap meat produced inside factories, untethered from the landscape.

Conclusion

"My God, my god, why have you forsaken me?"

You can see why farmers (average age: 57) aren't excited about the future. A final decade of equipoise before retirement seems unlikely. The only hope for continuity is that the removal of subsidies is offset by food price rises, which in turn must be greater than the rise in farm costs. Here's the dairy farmer I interviewed:

Hopefully things are on the on the up because the cost of everything is going up: our milk price has gone up 4p in in three months. Absolutely unheard of. Every penny to us is £15,000.

...

Fertiliser last year was 260 pounds a tonne and it's [now] up to 600 to 800 pounds.

If this doesn't happen, then the removal of the CAP-style subsidies will cause lots of farms to go out of business. And if meat taxes or carbon pricing schemes are introduced, even more farms - particularly pastoral farms - will be knocked out. Brexit will not deliver for those that make a living through these farms. Like the lamb of god, these pastoral farmers will be sacrificed to save us all.

It's not all bad, for those that have the resources and the will to change, the boutique and the rewilding farm models offer new streams of income. In the coming decades, huge amounts of capital will flow out of London on the hunt for sequestration projects, and British farmers are well-placed to capture that investment, by their proximity to the global financial centre, by their closeness to elite universities, and by the certainty of property and contractual rights in the UK.

The tasks that farmers do will change. Rewilding farmers will impersonate animals. Boutique farmers will have to learn new skills, such as winemaking and cheesemaking. The arable kingpins won't be outside much; they'll be in-front of a screen managing large numbers of staff and robots. It's all change.

But I may be wrong! Never underestimate the capacity of things to just kind of stay the same...

If you've enjoyed this newsletter, please forward it on.

If these emails are going to your spam, then either add my email (charlie@re-working.co.uk) as a safe sender, or reply to this email (feedback / abuse welcome!).

And if you aren't yet subscribed, please subscribe to receive the weekly newsletter. Thanks!

Postscript: assorted final thoughts

(1) If the carbon cost of shipping and flying is reduced, then in most cases the carbon footprint of foreign food will be less than British-produced goods. Why buy British cucumbers when they can be grown far more efficiently in Spain and shipped over? National pride? Food security? Surely both of those are subservient to net zero, the pursuit of which may turn the clock back to the 1930s, when we imported the vast majority of our food.

(2) Late last year, the EU's Farm to Fork food strategy passed the European Parliament largely unharmed by substantial agribusiness lobbying efforts. This plan both gives money to small farmers and represents a commitment to reduce the carbon cost of farming by 20%. Does this contradict the assumption that I made in the introduction? (i.e. that the EU's model of farming subsidies is incompatible with modern climate priorities). I'm not sure. I struggle with the idea that a system that pays enormous amounts of money to ruminant-rearing pastoral farmers can ever be effective climate policy.

Farmers were 53-45% leave-remain. This was less Brexity than you might expect given their average age (57) & education status (few graduates). ↩︎

https://www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/explainers/common-agricultural-policy#:~:text=The Common Agricultural Policy (CAP,to%20farmers%20in%20member%20states.&text=To%20increase%20agricultural%20productivity%20by,standard%20of%20living%20for%20farmers. ↩︎

dw.com/en/exposed-how-big-farm-lobbies-undermine-eus-green-agriculture-plan/a-59546910 ↩︎

National Food Strategy, p. 121. ↩︎