A two-parter on concrete additives (and friendship)

You can slow down the setting of concrete by adding dissolved sugar to the mix. The sugar forms a rough screen around the cement molecules and, for a time, it holds the water off, stopping the cement from crystallising. When cement molecules take longer to crystallise, concrete takes longer to set.

The sugar-and-concrete pairing has dangerous practical weaknesses. If you add too much (any more than 0.1% of total cement weight), then you might stop the concrete from setting entirely, or you might flash-set concrete, where the curing process happens so quickly and so incompletely that the resulting concrete is dangerously weakened.

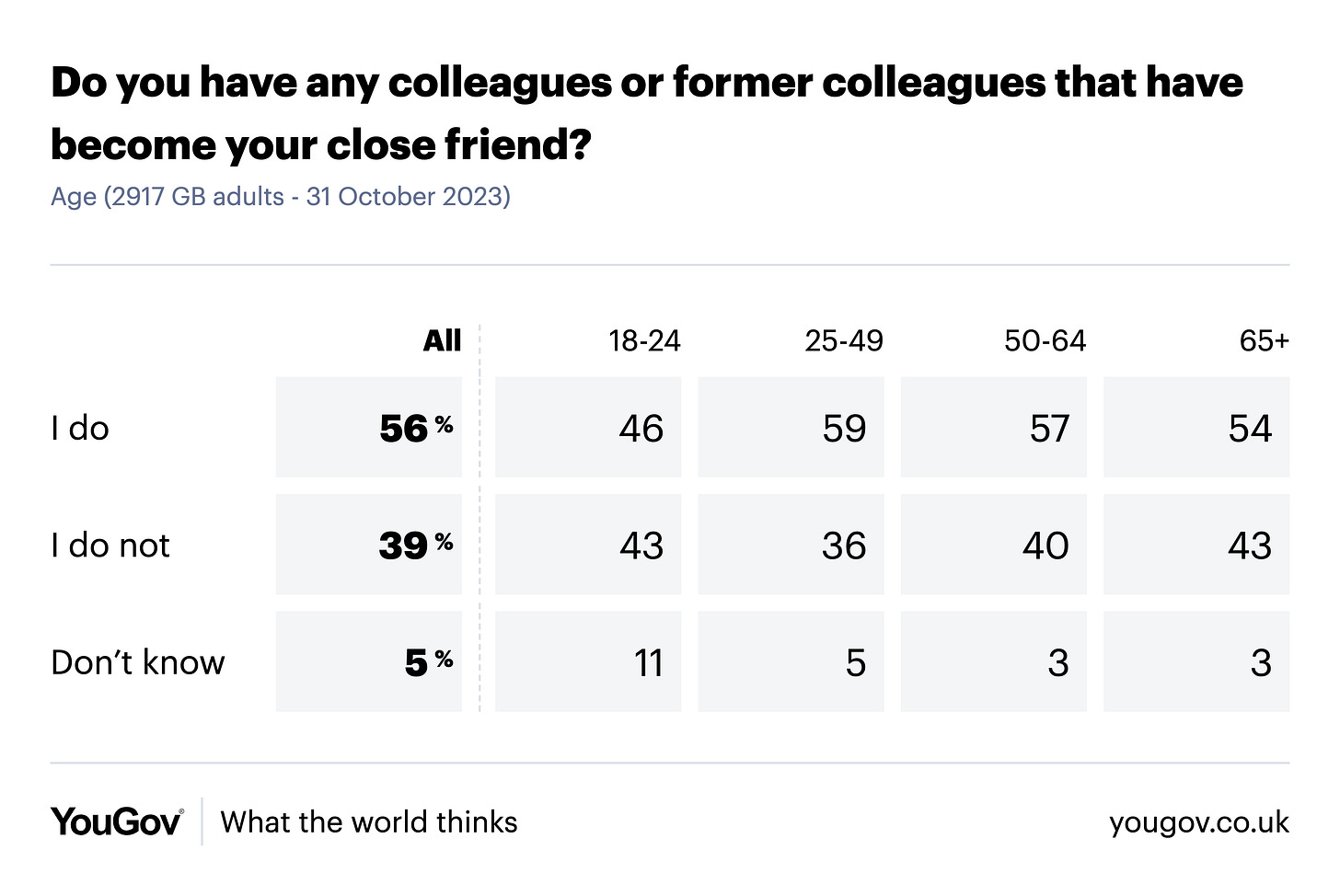

Sugar has practical weaknesses as an additive, but it has strengths as a metaphor. It conveys a certain situation well: where the presence of something inhibits the development of something else. Consider this table. It records the results of a YouGov poll which asked British workers ‘Do you have any colleagues or former colleagues that have become your close friend?’.1

The numbers show that time spent with colleagues yields a poor return when it comes to friendship. 39% of us do not have any close friends among colleagues and former colleagues. That figure rises to 40% for those between fifty and sixty-four, and to 43% for those over sixty-five. This is remarkable when you consider the fact that these two age groups have spent decades and God knows how many hours at work—all those conversations, all that effort, all those years, and yet not a single close friend. This is a clear example of sugar and concrete: our jobs inhibit the development of friendships.

On the face of it, the workplace is a good place for making friends. It is one of the few places in modern life where we spend extended periods of time (over an extended period of time) with people outside of our family. The workplace looms larger in respect of friendship as the other strands of public life become less important. Churches, community sports clubs, PTAs, WIs: they are all in long-term decline.

Perhaps it shouldn’t matter that many struggle to make a close friend over the course of a fifty-year career. Is it not a mark of having kept work at arm’s length from your inner self? Your job has already taken your time, why should it take your emotional life as well? Why not save your energy and vulnerability for those that you love outside of work? And is there not something to be said for being reserved in the workplace?

But among this friendless 43% many will not have intentionally willed themselves away from getting close to people at work. Instead, they will have tried but failed to make long-lasting friendships, and they will have failed because there is something within the nature of work itself that acts against friendship. What is that something?

A story that we often tell is that this workplace loneliness is tied to the atomisation of modern work. On this reading, our services economy is an Unreal City, where our work is intangible and devoid of meaning; where we are rootless, drifting from job to job every few years; where our interactions with our co-workers are mediated through and hollowed out by technology, each email and call and Slack message a lifeless caricature of a real conversation; and where the intangibility of our work makes promotion a reward for politicking rather than skill, with the resulting competition and envy stoppering any attempt at emotional vulnerability, the thing you need for friendship:

“You have to tell people that you’re amazing, because in an environment where you have all these big characters trying to show off over the tiniest of achievements, it’s those loud voices are the ones who succeed and progress. In that atmosphere, you have to compete.”—Management consultant

There’s a bit of truth to all that stuff. It is obviously harder to maintain close friendships when you leave jobs every four years. What’s more, the increasing unreality of work does seem to have made friendship more difficult: the percentage of Americans who have a best friend at work has fallen 5% since the pandemic.2

But work is not just office work. What about this farmer, whose relationship with her family was corroded by work?

“When we were all working together, I saw my parents and brothers nearly every day. And then when you see them at Christmas, you don’t give them a hug or a kiss. When my husband’s parents or sister visit, they haven’t seen each other for months, so they hug and kiss and they’re genuinely pleased to see each other, whereas farmers…it’s a different relationship, and I think it’s a healthier one when you’re not working together.”

There must be something more essential at play, like the fact that work introduces serious and weighty things into the human relationships it touches—responsibility, money, status, and, above all, power.

These things make workplace friendships conditional. We can be friends provided that: you are on my side; we are on the same rung of the company hierarchy; you don’t order me about; you don’t make me look bad; I don’t have to tell you off; and so on. Eventually, one these conditions will be broken and the friendship will slowly, or quickly, wither away. The 43% of over-sixty-fives must have had many of these friendships, each with a set of conditions that represented a particular moment in time, where the two colleagues were at a similar place in their careers. In most cases, such conditions cannot hold. One person gets promoted or leaves the company; the conditions are broken and the friendship fades.

There is an exception: work that is all-consuming and dangerous; work where you are away from home for long stretches or where you are dealing in life and death. This work seems to send down deeper roots when it comes to friendship.

“…if there were a war tomorrow and I could go back with the people I was on tour with—my amigos—I’d go back again tomorrow. It sounds really cliché and cheesy, but it was a band of brothers. The other day, for instance, it was the first time I’d seen one of them in years, but it was like we’d never left each other. “—Soldier

“As midwives, we are each other’s counsellors. If we were going to therapy, it would cost the NHS an absolute fortune. It’s the understanding you get from your colleagues that you don’t get elsewhere. Your friends and family won’t understand what it’s like. But with a colleague, we’ll go for a walk and talk about the things that have happened.”—Midwife

“Working in a crew, it’s working with a bunch of guys that are trying to reach the exact same goal: everyone wants to get home safely. There’s also no point in having an argument with anyone because you’ve got work together for twenty-one-days’ solid. There’s a sense of brotherhood.”—Floorhand

Underneath all of these friendships is the sense that the work is so awful and profound that only your colleagues can truly understand how it affects you. The friendship that results from this shared experience seems to outlast the petty conditionality of ordinary workplace relationships.

This higher state is the essence of things like brotherhood and sisterhood, and it is also rare. Most of us, living dull lives, are in with a good chance of being among the friendless 43% when we retire. We shouldn’t like those odds. They tell us that work cannot be relied upon as a source of close friendship and, in turn, cannot be relied upon as a source of those meaningful relationships that are the key to a happy and fulfilled life.

This isn’t necessarily a problem, particularly if you are able to find friends and a sense of self outside of work. But today’s climate seems to be drying up those other sources of friendship and identity. Most of us now give our leisure hours either to a screen or to individual pursuits (compare, for instance, the rise in gym usage to the decline of sports clubs). Communal pursuits outside of work—religion, political organisation, drinking—have become less important to us. Work is all too often the only friendship game in town.

The cultural changes in the workplace in the last twenty years are, on some level, a response to this new reality. If work is the main way in which we socialise and exist out there in the world, then it is sensible to make work look more like friendship, or at least a sanitised version of friendship; this is the idealised Californian cheerfulness that now runs through the office, the language of folks, community, inclusivity, and we should set up a new slack channel to post pictures of our pets.

All of this may soften the edges of the many obstacles to friendship in the workplace, but I’m not sure it can ever remove them. But what do I know? The next newsletter is about the history of concrete additives, and an interest in concrete necessarily rules you out of any conversation about how to make friends.

YouGov. 'Survey Results for October 31, 2023:’ Do you have any colleagues or former colleagues that have become your close friend?’ YouGov, October 31, 2023. https://yougov.co.uk/topics/society/survey-results/daily/2023/10/31/de06d/3

Gallup. "The Increasing Importance of Having a Best Friend at Work." Gallup, 2023. https://www.gallup.com/workplace/397058/increasing-importance-best-friend-work.aspx.