canteen: closed

The story of workplace canteens in the UK is one of decline. In 2015, a survey of 351 workplaces found the following:[1]

The works canteen has continued to decline in UK workplaces. Less than half (47%) of 351 union reps said their workplace had a canteen. That is down on the 56% of the 254 union representatives responding to a November 2010 survey and well down on earlier surveys when the proportions were 66% in 2000 and 82% 20 years ago in 1995.

The real figure will be much lower: companies with union reps are more likely to be the sort of workplaces that have canteens.

what happened to workplace canteens?

If we start with the birth of canteens, we should be better able to understand their death.

Before the First World War, the provision of canteens was limited to factories that had philanthropic employers or that were in some sense dangerous, like arsenic works.

The First World War brought new power to the industrial workforce. If the unions were to have gone on strike, it would have brought the British war effort to a halt. Such a strike could not have been broken by imports from abroad (u-boats) or by local strike-breaking labour (any excess manpower was in Flanders).

Workers had leverage: they could name their price when it came to wages. This led the state to seek out ways of blunting the sharpness of future pay demands. Improving productivity was one approach, and here canteens proved successful - factory workers do more when rested and fed (a stunning insight). The number of canteens increased ten-fold over the course of the war. [2]

A similar process played out in the Second World War. Starting from a higher base, the number of canteens doubled to c.11,000 by war's end.[3] Outside of the factory, workplace canteens were accompanied by c.2,000 British Restaurants, state-run communal kitchens that served millions of meals a week between 1940 and 1947, and all for a maximum price of £1.34 in today's money. There were twice as many of these restaurants as there are Starbucks in the UK today. It's strange to think that the state homogenised the British experience of eating decades before American corporations did.

Workplace canteens are the creation of an industrial world. They spread when employees have the whip hand, and where there is a real concern that, without the canteen, workers would not eat enough to work properly. When these conditions ceased to exist after the Second World War, so too did canteens.

Fifty years of deindustrialisation: workplaces are smaller and less dangerous now. Therefore, the relative cost of a canteen is higher and the need is lower. Eating your lunch in front of a screen is safer than eating it on the shop floor of an arsenic factory.

Thirty years of loose labour markets: a good canteen is a cost for employers and a benefit for employees. Why give an inflation-beating pay rise if you don't need to? Why spend a lot of money on a canteen if you don't need to?

We're no longer hungry: there is no need for a workplace canteen. It is easier than ever to consume calories quickly on your lunch break. Microwaves. Supermarkets. Coffee shops. Fast food shops. None of these things existed in the golden age of canteens.

Our expectations have changed: consumer capitalism is all about unbounded choice. A canteen with one or two options seems terrible compared to the high street or Deliveroo. And if we demand more choices from the canteen, then it becomes so expensive that we might as well eat out anyway.

Royal Mail still have subsidised canteens, but people are stopping using them because of the lack of choice. This is what a postal worker told me:

The canteen is dying off. It's dying off slowly.

They do sausage, beans, eggs, you know you name it, but a lot of people now are porridge and apples for breakfast.

I fall foul of that. I don't really have fry ups anymore. As much as I love em... You've got to walk round for hours with that in you.

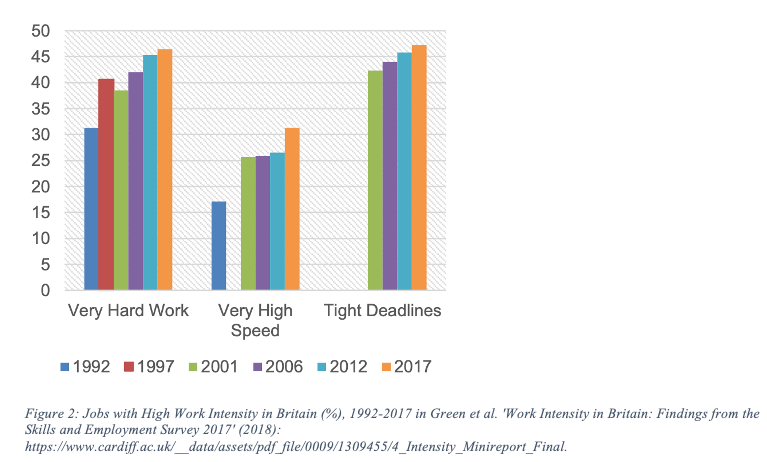

We feel busier: we eat at our desks more than we used to. There's an anxiety about stepping away from one's desk that never used to be there, which is probably a symptom of work becoming, or at least feeling, more intense:

We gain certain things by living canteenless lives - greater choice, more time to work, trips outside the office - that sort of thing. But, of course, there's a social loss in our failure to devote time each day to sit and eat with our colleagues. If you were to take the time to add it all up, you'd find that in each workday there is far less of all the good and fun things that flow from shared human experience - laughter, gossip, plotting, flirting, consoling and the like. If we stopped using canteens because they felt too much like grey homogeneity, then we've replaced the greyness with an even darker individualism.

the Google canteen revival

Many haven't been so hasty in ditching the communal lunch. Before Covid, it was against the law to eat at your desk in France. There has also been a canteen arms race in those industries that are anxious either to retain their staff or to keep them in the office for longer. Investment banks, law firms, FAANG: all have kept the canteen dream alive.

Newly-tightened labour markets may arrest the canteenic decline. Employees can make demands of their employers that they couldn't make in 2019: why not ask for a good canteen? I think I'd work for any employer, in any job, if they did a hot main and a salad for, say, half the price of a supermarket meal deal.

Besides being something that employees might want, canteens are useful to employers in other ways. The endless research about healthy lunches helping schoolchildren study applies to office workers, too. And to this pile of pro-canteen research, you can add the many studies about the benefits of communal eating.

If flexible working means that employees spend less and less time together, then perhaps the time they do spend in the office should be meaningful, and there's nothing more meaningful than breaking bread together.

That's all from me. I hope you all have a good week.

Charlie

Contact me: charlie@re-working.co.uk

If you've enjoyed this newsletter, please forward it on.

And if you aren't yet subscribed, please subscribe to receive the weekly newsletter. Thanks.